Back to 1909 with Trump's Tariffs

Global trade war explodes...

OUCH, says Frank Holmes at US

Global Investors.

Global markets are in freefall in response to

President Donald Trump's

universal 10% tariff on all goods being imported into the US, with as many as 60 countries facing

"reciprocal" tariffs on top of

that.

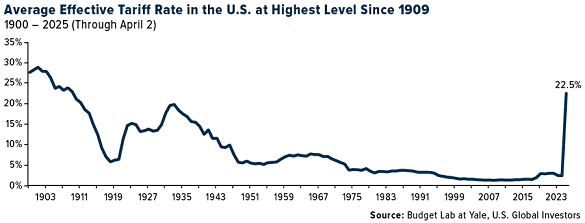

When we combine all new tariffs in 2025 so far, including the raft of

reciprocal tariffs announced last

Wednesday, we're looking at an average effective rate of 22.5%, according to Yale's Budget

Lab.

That's the

highest such rate since 1909 − the same year that President Howard Taft proposed the idea of an income

tax to Congress.

As I have pointed out

before, tariffs are a type of tax paid for by domestic import-export companies, who often pass the

additional cost on to consumers.

This can turbocharge domestic inflation.

Tariffs can also lead to full-blown

trade wars, as we saw in the

federal government's previous attempts to raise revenue through the taxation of imported

goods.

The

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, enacted in 1930, is widely believed to have exacerbated the effects of the

Great Depression, as global trade

tanked a whopping 65%. A few decades prior, then-Representative William McKinley's tariff act triggered

retaliation from other

nations, leading to higher prices for US consumers.

(If you need to brush up on

your Smoot-Hawley history, I

recommend the famous "Anyone? Anyone?" scene in 1986's Ferris Bueller's Day Off.)

As was the case then, we're

already seeing retaliatory tariffs. China announced that it will impose a 34% duty on all goods imported

from the US. If this weren't

enough, automobile imports face a steep 25% tariff. Trump claims he "couldn't care less" if foreign

manufacturers raise prices for US

consumers, and from the looks of it, they may need to − and significantly so, in some cases.

Mitsubishi, for

instance, will need to increase the price of its vehicles by more than 20% here in the US to offset the

new levy, according to

estimates by CLSA.

The manufacturer expected to fare the best under this tariff

regime is Tesla, whose supply

chain is well-integrated in the US. More than 62% of the company's facilities are located domestically,

with approximately a quarter

of its suppliers also based in the US, according to Bloomberg data. By comparison, fewer than half of

Ford's facilities worldwide are

currently located in the US.

This could be constructive for Tesla, whose stock

has lost over half of its

value since its peak in mid-December, making it one of the worst performers of the year so far. The

carmaker's quarterly sales fell a

significant 13% in the first quarter compared to the same period last year, due mainly to political

backlash against CEO Elon

Musk.

When it comes to new home purchases, bad economic news could be good

news. Mortgage rates generally

track the yield on the 10-year Treasury, which dropped below 4% on Friday due to concerns about the

trade war. Bond yields generally

fall when prices rise.

Granted, home prices in the US are still hovering near

record highs, but current

homeowners may be able to refinance sooner than expected.

Lower yields are also

good for gold. Because it's a

non-interest-bearing asset, gold starts to look more attractive as yields fall, especially when

inflation remains historically

elevated, as it is now. The 10-year yield is nominally 4.1% right now, but when you factor in the 2.8%

headline inflation rate from

February, the real yield is closer to 1.3%.

If yields fall further or if

inflation jumps higher due to

tariffs, we may end up with negative real yields, which have historically been bullish for gold

prices.

The

yellow metal is trading down as it's swept up in the broader selloff, and I believe investors should

strongly consider buying these

dips. Gold just notched its best quarter since 1986, ending March at $3123 per Troy ounce, and there

could be further upside momentum.

Email

us

Email

us