Basel 3, QE and Bank Reserves

Why QE didn't devalue the Dollar...

CENTRAL-BANK balancesheets are a function of the "demand for money", writes Nathan

Lewis at New World

Economics.

This "demand" basically taking two forms: banknotes and

coins among the general

public, and bank reserves (deposits at the Federal Reserve) among banks.

It is

fairly easy to see that the

public holds exactly the amount of banknotes that it wishes, and no more. At any time, if people wanted

to hold more banknotes, they

could go to their nearest ATM machine and get more.

Since bank deposits are

much larger than banknotes

outstanding, in general it is very easy to acquire more banknotes. Conversely, if people hold more

banknotes than they would like,

they would deposit them in banks. If banks ended up with a consistent oversupply of banknotes – pallets

and pallets of banknotes that

nobody wanted – they would trade them with the Fed/Treasury for bank reserves.

Thus, the total base money –

of bank reserves plus notes and coins – is a fixed number determined by the Federal Reserve, but the mix

is determined by private

behavior.

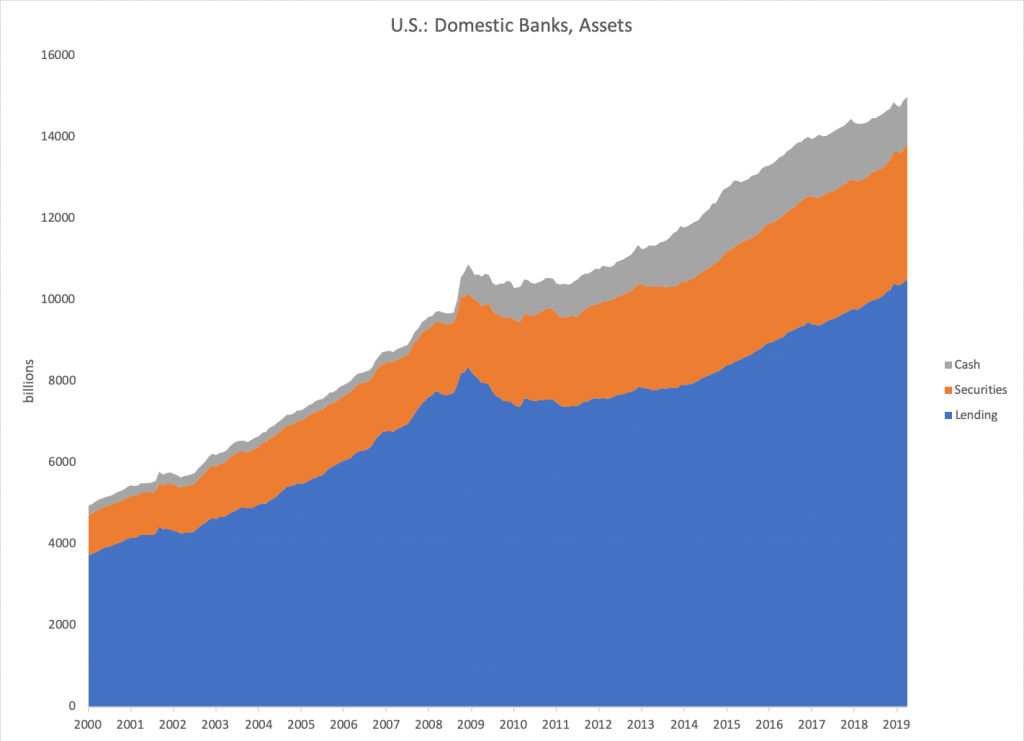

I have characterized the increase in bank reserves since 2008 as a

matter of banks wanting to hold

more reserves. This is why this very large increase in supply was not met with a very large decline in

the value of the currency,

which comes about when supply is in excess of demand.

Broadly speaking, this

supply met increased demand from

banks to hold reserves on their balance sheets. This basically represented a return to "1950s-style"

norms in banking, where bank

reserves would be about 10% of total assets. For US domestic banks, the ratio is about 8%

today.

Huge

increase in

bank reserves since 2008, but also freakishly low levels before 2008.

This

increase in reserve demand among

banks makes sense from a business perspective, independent of regulation (for example, the very large

holdings of bank reserves in the

1930s, far in excess of regulations), but it has also been reflected in regulation.

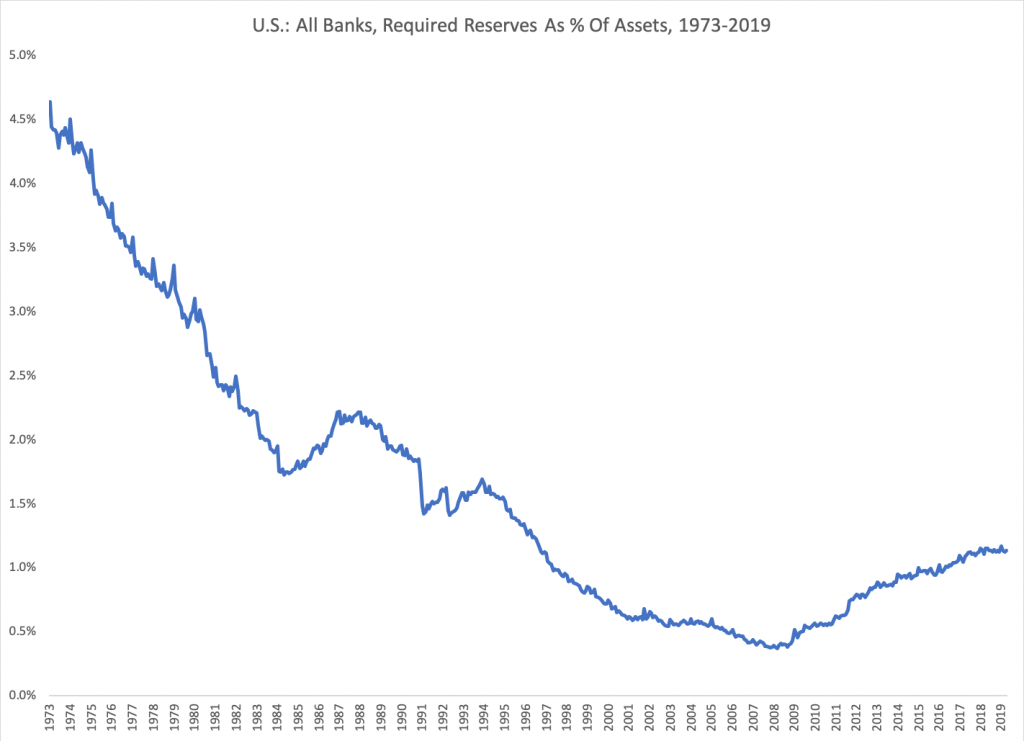

Federal Reserve reserve

requirements haven't changed much, and are still very, very low. However, Basel III requirements have

changed a lot.

Basel III was agreed on in November 2010, when the 2008-2009 crisis was acutely remembered.

In general, I like the return

to "1950s-style" reserve holding patterns among banks, so I am also broadly in favor of the Basel III

changes.

The Basel III requirements have two aspects, the "Liquidity Coverage Ratio" or LCR, and the

"Net Stable Funding Ratio" or

NSFR. They are complicated. The important thing is how it plays out in real-world action.

The interesting

thing is that these requirements have been slowly ramped up, and had full implementation only in

2019.

Take

J.P.Morgan Chase's latest annual report for instance. We find that the "high quality liquid assets"

amounted to $529 billion at the

end of 2018, which included $297 billion of "eligible cash" which "represents cash on deposit at central

banks, primarily Federal

Reserve Banks." This produced an LCR of 113%, which was a little (13%) in excess of the Basel III

requirement of 100%. Since a little

cushion is necessary to keep from falling beneath the requirements, 113% is about the "effective minimum

requirements."

The total assets were $2,622 billion. So the ratio of central bank deposits ("bank

reserves") to total assets was $297

billion/$2,622 billion, or 11.3%.

In other words, big banks like JPM are

holding large reserves because they

have to, to comply with Basel III, and also because – I argue – that it is a good idea.

Obviously, if banks

are going to comply with these requirements, then these bank reserves must exist, and that is why

central bank balance sheets, in

particular the Federal Reserve in this case, are larger than they were in the past.

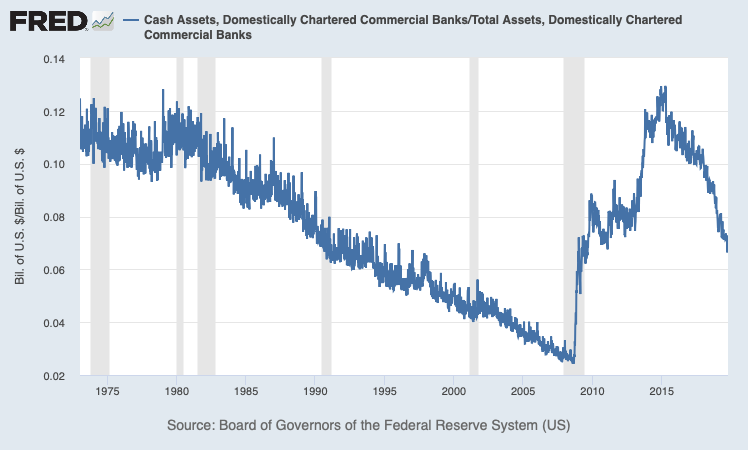

In the past, "cash

assets" were a mix of Federal Reserve deposits and other instruments, but today they are basically Fed

deposits exclusively. This is

also the way it should be in my opinion, and also the way it was in the 1950s. Here we see that the

recent bank reserve/assets ratio,

among domestic banks, is about 7%. This is way below the 11.3% that is basically a requirement at

JPM.

In

short, "cash assets" (bank reserves) have been plummeting. They are way above the levels of early 2008,

but not very high if we now

expect banks to hold 10% of assets in the form of bank reserves at the Fed.

Email

us

Email

us