Banking Crash? Fed Just Raised Rates Above Entire Treasury Yield Curve

Recession now racing this way says US bond market...

I'M NO FAN of 19th Century doorstoppers running to hundreds of pages with

a cast of

thousands, writes Adrian Ash at BullionVault in this note first shared with readers of the Weekly Update email on

Monday.

But

even if you've never read Anna Karenina, you probably know the opening line, if not the sad

ending:

"Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

Now, being a financial pundit

in need of an opening line today, I wanted to spin this for the banking sector here in spring

2023.

But

writers on deadline rarely stumble across unique ideas, and someone smarter than me just cut to the

chase...

...asking Microsoft's ChatGPT for

help:

"All well-run banks are alike; each poorly run bank is poorly run in its own

way."

I, for one,

welcome our new robot overlords. So let's go with that.

Just how poorly-run

were the banks to fail so far or

face collapse in this 2023 scare?

Roughly

speaking, a bank takes in deposits while making loans.

To turn a profit, it

just needs to pay less interest

on the deposits than it charges on the loans.

Simple, right? Apparently

not.

Silicon Valley Bank

Took in too much cash from too many tech start-ups who

were flush with money and

didn't need any loans.

So to generate income, SVB bought long-dated bonds,

mostly US government debt. Those

Treasury bonds are the safest thing in the financial world...up

until they sank in

price as inflation jumped and the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest pace in pretty

much ever.

Net result? SVB's loans (to the government) weren't worth what its depositors were owed.

Cue a run for the exits when "a

small number" of venture capitalists took to WhatsApp and shouted

'Fire!'.

Signature Bank

Lent money on New

York real estate (among other

things) while taking in lots of cash from crypto firms, even building them a payments platform (called

Signet) so that the crypto firms' customers could turn magic beans into real Dollars

24/7.

Like SVB,

that 'concentration risk' of too many customers all in the same business all at the same time meant that

its depositors all started

needing their money back when interest rates rose and crushed crypto. Lots of its borrowers suddenly

started looking flaky for the

very same reason.

Cue a rush for the exits, again led by bigger depositors

spotting that they might need but

hadn't got a government guarantee. Because, to quote Investopedia, "Signet

required a minimum account

balance of $250,000; FDIC insurance caps out at $250,000."

First

Republic

Had a

lot of deposits bigger than the US insurance limit, again making it vulnerable to a rush for the exits

if people started to worry. It

then parked a lot of those deposits in long-term bonds, suffering a steep loss of value as bond prices

sank so that yields could rise

alongside short-term interest rates.

Cue a rush for the exits because, well,

just because. FRC's financial

results for 2022, released in mid-January, actually looked pretty strong at first glance...

..."another terrific

year of safe, consistent and

organic growth" according to its CEO.

But with over 2/3rds of the money it held

on deposit uninsured by the

FDIC guarantee, that cash

still ran for the door, and the share price slumped, as the banking scare took hold and

spread.

No, it doesn'y help that news of massive

salaries for the founder, his brother-in-law and his son is now coming out. And it really

doesn't help that the $30bn

which 11 major US institutions put on deposit at FRC as a (government-driven) show

of

confidence did nothing to stem the share price slump last week.

Credit

Suisse

Very much bigger than the first two US casualties or crisis-hit FRC above,

so it's harder to summarise.

But in short, CS was just very badly run...flailing its way through any number of scandals, swapping its

CEO, announcing a whole new

plan, spooking its investors, and managing to make a

monster loss in 2022 of

more than $7 billion, pretty much equal to what its Swiss rival (and now owner) UBS made

in profit.

Scandals weren't

new at

CS however, and it was far from alone in scandalous banking. But a rush for the exits started last

autumn, with depositors pulling out

$120bn in Oct-Dec alone. The coup de grace then came 2 weeks ago, when the boss of the bank's biggest

investor...Saudi Arabia's

state-owned Saudi National Bank...said "No,

absolutely

not" when asked if he would stump up any more cash to keep it in business. (He has since

'resigned' for 'personal

reasons'.)

Contra Count Tolstoy then, a couple of common points stand out at

these unhappy banks.

First, concentration risk: Is your bank serving all the same type of

customers, whether on its loans or

deposits? Just as importantly, how much of the deposits aren't covered by insurance? Big money runs

fastest.

Second, regulatory pushback or failings: Credit Suisse kept blotting its copybook,

while both Silicon Valley and

Signature wanted to avoid the hassle and costs involved in the rules and oversight of becoming a very

big bank worth more than $50

billion...a level set by the post-financial crisis Dodd-Frank Act. But rather than capping their size,

they lobbied to get the

threshold raised! The Trump administration obliged

in

2018, raising the minimum level for "enhanced oversight" to $250bn.

Third, don't simply

trust in longevity or brand. Credit Suisse was founded in 1856 and became synonymous with the

stability, security and

safety of the mountain-ringed nation. SVB had been around for almost 40 years, growing to become the

16th largest bank in the US by

this New Year (but repeatedly telling lawmakers that it wasn't all that big really, and not

big enough to

warrant a big-bank regulation).

First Republic has been around since 1985, and

while Signature had a

more chequered history, it had grown since

launch in 2001 to the 19th largest US bank, even bagging former Republican Barney Frank as a member of

its board of

directors.

(Yes, THAT Barney Frank, one half of the post-financial crisis'

Dodd-Frank Act, which claimed to

make US banks much safer by fighting the last war. He's now

mad

as hell that the feds shut down his bank and sold off its assets...well, those assets that anyone

might want to buy...just

because it threatened to spark a sector-wide panic.)

Okay, so that's the scare

so far. What comes

next?

"To be crystal clear...Deutsche is NOT the next Credit Suisse."

So

said a research note picked

up by pretty much every financial

journalist late last week as shares in Germany's No.1 bank fell and fell again.

And in contrast to the

flakier little banks above, Deutsche says that 76% of its

German retail deposits are covered by the Eurozone and German government insurance schemes, with 1/3rd

of its total deposits covered

worldwide.

Moreover, as the Wall Street Journal says, "The bank is solidly profitable,

has the strongest capital

ratios since the late 1990s, and has lower interest-rate risk than some US regional banks.

"[So while]

Deutsche Bank itself is also no stranger to tough times, it is far more advanced in its turnaround than

Credit Suisse was when

confidence evaporated."

For now the gold market seems to agree, easing back

rapidly from last week's

banking-scare peaks as the depositors' rush for the exits takes a breather and European and US banking

shares rally.

Maybe this pause in fact marks the end, and the 2023 banking crisis will have lasted for

just a few weeks in March. But

some people said that about Bear Stearns 15 years ago, and even among the compliant, well-diversified

and well-capitalized banks

today, the real trouble hasn't yet hit.

Because the loan-book hasn't yet turned

sour.

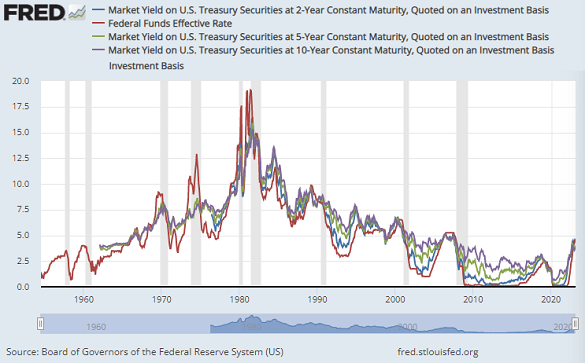

Squint hard enough at this chart and you can

see how...every time a US

economic recession is about to begin (as marked by the vertical dark grey bars)...the red line has risen

above all the

others.

That red line marks the US Fed's key interest rate, the Fed Funds rate.

The other lines mark the

annual yields offered to new buyers of 2-year, 5-year and 10-year US government bonds.

We could add the rate

offered by 30-year or 12-month, 6-month or 3-month bills, too. It wouldn't matter. Those rates

also went below the Fed's target interest rate just before a US recession

began.

And for reference, following last week's action...

...when the Fed Funds rate

was raised to a ceiling of 5.00% while the banking scare sent US bond yields sharply lower yet

again...

...the Fed's key interest rate is now higher than the yield on any US Treasury bond or bill once

again.

This

kind of picture, where short-term rates come above longer-term rates, is known as an 'inverted yield

curve'. Inverted because, more

normally, long-term lenders get a bit more in annual interest than short-term lenders, to compensate for

the extra time risk. And the

gap between 10-year and 2-year US bond yields has now been inverted non-stop for 9 months, shouting

"Recession!" at passers-by because

it suggests that, sometime in the future, US interest rates will need to fall.

The track record of the 10-2

measure isn't perfect, however. It's called recession a little more often that a US recession has

actually followed. But it's now

half-a-year since the 10-year minus 3-month yield curve also flipped negative, and now that the Fed's

overnight rate stands above

every yield you can get from a US Treasury bond, note or bill, the market is screaming "Recession!" like

no time since, well, the eve

of the last economic downturn.

Whatever the mechanism or process by which an inverted yield curve turns into an

economic downturn, this

feature...where the Fed raises its interest rate above anything offered in the Treasury debt

market...has preceded each of the last 8

recessions in the world's largest economy, including (weirdly) even

the Covid Crash of 2020.

It's just happened again. And some poorly-run banks

were already in

trouble.

"There's something wrong! The bank won't

give someone their money," says a

lady queuing at the bank in Mary Poppins, half-hearing a commotion about tuppence belonging to

a child.

"Well I'm going to get mine!" says the lady next to her. And so begins the near-collapse of

the Fidelity Fiduciary

Bank.

It all sounded quaint and Victorian back in 2007 when Northern Rock failed, and it seemed

absurd when

Bear Stearns went in March 2008, nine

months after it made the headlines over the pile of toxic debt

derivatives it held. But in the week ending Wednesday 15 March 2023, depositors at smaller US

banks pulled out a record $107bn from their

accounts...

...almost what global giant Credit Suisse lost in the last 3 months of 2022 combined.

In the final analysis,

a banking run means that depositors...right or wrong...fear that the bank's debtors aren't going to

repay their loans, leaving the

bank without enough cash to repay its savers.

This bad genie is now freed from

his bottle once more. Loans

across Western banking markets haven't yet started to

sour. But the bond market says a US recession is racing towards us.

Y'know,

like a steam train.

Email

us

Email

us